In Japan, the true meaning of the word “carpentry” differs significantly from the associations an average Westerner would get at the mention of anything carpentry-related. But moreover, this unusual difference is not merely related to the fact that Japanese carpentry has been around for more than 1000 years.

Actually, there is deep and enchanting magic surrounding traditional Japanese carpentry, and it is surely no wonder why it managed to gain worldwide acknowledgment.

It is only fair to refer to Japanese carpenters as gifted artists, for Japanese carpentry is truly an art form itself. Certainly, that’s closely related to the very roots of Japanese carpentry.

Back in the pre-industrial era when carpentry in the Country of the Rising Sun was starting to develop, the gifted woodworkers engaged in the art of Japanese carpentry would highly rely on understanding the forces of nature.

To be more specific, Japanese carpentry has evolved around the profound and precise interpretations of the rhythms and cycles of nature by the natives.

Back in those days, those who wanted to become master carpenters had to love and respect the craft immensely, because hard work alone was not enough to define all the great skills needed to practice Japanese carpentry.

Japanese Carpentry 101: What Does it Take to Become a Master Carpenter?

For a start, the Japanese word for carpenter is Daiku. In Old Japanese, there were two terms for Daiku, namely Ootakumi and Ookitakumi.

Ultimately, all Japanese who practiced the core values of Japanese carpentry would share the same basics of woodworking, as well as identical vocabulary and methodology.

However, there are four carpentry professions that have become distinct in Japanese carpentry.

1) Miyadaiku

Miyadaiku carpenters are the ones involved in the building and construction of the notorious Japanese shrines and temples. Moreover, Miyadaiku carpenters were the masters of the incredible Japanese joinery techniques.

The superb wooden joints crafted by the Miyadaiku masters have proved to be one of the most stable joints ever known to humankind.

Thus, some of the oldest wooden structures in the world that managed to survive up-to-date are attributed to the art of Japanese carpentry.

2) Sukiya-Daiku

Sukiya-daiku masters were involved in the construction and building process of teahouses, as well as various residential houses.

Japanese teahouses were designed by following strict rules. Then again, the harmony between people and nature was highly valued. Thus, no additional paint or varnish of synthetic origin was applied to any of the wooden surfaces. Nevertheless, these surfaces were hand planed.

Another important aspect of the work of Sukiya-daiku masters was measuring the proportions with absolute precision. As a rule of thumb, the posts and beams of a Japanese teahouse had to be proportional to the size of the framed room.

3) Sashimono-Shi

Sashimono-shi carpenters were the ones in charge of the furniture making process. In fact, “Sashimono” stands for a traditional Japanese furniture making technique.

Similarly to the construction process of temples and teahouses, the Sashimono technique is focused on joining the pieces of wood without the use of any nails.

Sashimono-shi carpenters had to learn how to “read” the grain perfectly. Thus, acquiring the ancient knowledge could take many years before the carpenter could finally start “speaking” the language of the wood.

4) Tateguya

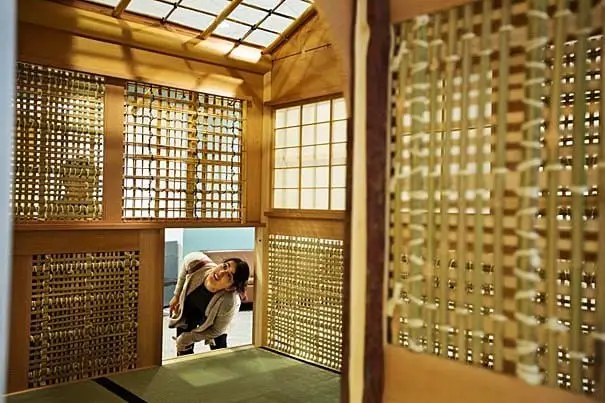

Tateguya carpenters were solely engaged with the process of interior finishing. To be more specific, a Tateguya master would be in charge of the Shoji and Ranma. Interestingly, the skills of a Tateguya master can be compared with those of an ébéniste.

ébéniste is the term used to describe the art of French cabinet-making and refers to the very practitioners of the craft. Meanwhile, Tateguya is often translated as Japanese cabinet-maker.

Interestingly, according to the Japanese, the elaborate process of finishing and joining each part of a particular construction by referring to the art of cabinet making in the following way: “… [] as if a cabinetmaker built an entire house by hand. The quality extends, not just to the timberframe itself, but to every visible surface and detail… []”

Above all, becoming a Daiku is not an easy job for it requires extreme dedication, passion, and nonetheless, talent. In recent years, the legacy of ancient Japanese carpentry has been threatened by numerous challenges.

Behind the Curtains of Japanese Carpentry: The Invaluable Insights of a Daiku Master

Matsuura, who is a descendant of the craft of Japanese carpentry was interviewed by Japanese journalist Asako Murakami, with the article being published by the Japanese Times.

Matsuura was entitled “national asset as a technical expert” by the central government all the way back in 1999. He earned the unique designation for possessing woodworking techniques that are in dire need of being preserved for the next generations.

Shoji Matsuura has worked as a Daiku for over 50 years and was engaged in the restoration of 28 cultural assets, as well as 5 national treasures across the Country of the Rising Sun.

Matsuura highlighted the importance of developing a deeper and better understanding of the wood, and that understanding is, then again, closely related to acknowledging the laws of nature.

“The techniques for constructing wooden buildings in the past greatly surpass those of today. Wood used to be broken along the grain. But once people started using a saw, they ignored the grain and failed to make the most of wood’s characteristics. People used their brains more when fewer tools were available.”

Another crucial and probably surprising aspect of ancient Japanese carpentry that is victimized by the global issues of the 21st century was also pinpointed by Matsuura.

According to Matsuura, the Japanese forests fail to provide the same high-quality wood material as they used to, and there’s a perfectly logical explanation behind this problem.

“Replanted trees are not good as they are coarse-grained. Those which have stood for many years withstanding wind and rain are those that are good quality.”

Looking into Japanese Joinery (or What Makes Japanese Joinery Unique?)

Above all, Japanese joinery is often referred to as an art form because it managed to bring together pieces of wood in an incredibly perfected manner.

Ultimately, without the use of any nails, power tools, or screws, the Japanese have polished their carpentry skills at joinery to such an extent that the joined pieces of wood appear as if never actually touched by a human’s hand.

Dovetailing is probably one of the most famous types of joinery that were utilized by the Japanese carpenters (Daiku masters).

However, experts believe that many joinery techniques are still unexplored and it is only a matter of time before we get to understand the legacy of the ancient Japanese carpenters, embedded in the complex structures of shrines, teahouses, and temples.

And indeed, the Japanese joinery techniques were fined and honed within the course of entire millennia (and, in fact, even more).

On another note, not only the techniques but also the tools of the Daiku masters played a crucial role in the ancient craft of Japanese carpentry.

What are the Authentic Tools Used by the Japanese Carpenters?

Kanna (Japanese plane)

The traditional Japanese plane consists of a laminated blade, securing pin, and a sub-blade, attached to a wooden plank known as dai.

In archaic times, long before the invention of kanna, another type of Japanese plane was used. The so-called yarigana highly resembled a spear.

Nokogiri (Japanese saw)

The traditional Japanese saw possessed amazing blades that were way thinner than those used in the West.

That was possible because of the unique cut style of the saw. Rather than being utilized through the application of a push stroke, the nogokiri works through the power of a pull stroke.

Nevertheless, the process of making traditional Japanese saws by hand was one that required absolute precision, as well as a great amount of patience and time. As a comparison, making chisels or planes is considered an easy task when taking into account the difficulty of creating a saw.

Nomi (Japanese chisel)

All in all, there are many different types of Japanese chisels, and each of these served a particular purpose only.

As a rule of thumb, most of the authentic Japanese chisels were made with a mind to working well on softwoods since softwoods are most widely available in the country.

In the case the daiku masters had to work with hardwoods, the chisel’s bevels would be first steepened carefully.

Genno (Japanese hammer)

The types of hammers that are typical for Japanese carpentry vary depending on the specific purposes of the craft. Thus, some hammers are solely used for chisel works.

On the one hand, there are also hammers used for the positioning of hand plane blades. On the other hand, there are hammers that serve only for pulling and hammering nails.

Sumitsubo (Japanese inkpot)

The ink used to mark straight lines is soaked in silk wadding.

The very thread of the sumitsubo is carefully tied to a rounded piece of wood. Next, a needle is fixed at the very end to ensure that the carpenter can hold the sumitsubo in such a manner that the needle can be fixed onto the surface and determine the position of the thread.

Kiri (Japanese gimlet)

The kiri is labeled as one of the most difficult tools to master in the craft of Japnese carpentry, even though the kiri appears rather straightforward to use.

Meanwhile, the kiri is one of the staples of Japanese carpentry since it is utilized at the very beginning of hollowing out a mortise joint. For this purpose, the kiri is generally applied to bore circular holes in timber.

Marking and Measuring tools

Most importantly, there are many different measuring and marking tools that have a special place in the art of Japanese carpentry.

Some of these include the Sashigane (the well-known carpenter’s square), the Kiridashi (marking knife), and the Sumisashi (bamboo pen), to name a few.

When it comes to the most commonly used types of lumber in the ancient craft of Japanese carpentry, these include but are not limited to Kiri (Paulownia tree), Keyaki (also known as Japanese zelkova or Japanese elm), Hinoki (an endemic type of Japanese cypress tree), Akamatsu (Japanese red pine), Camphor Laurel (commonly known as camphorwood), Sugi (Japanese sugi pine or Japanese cedar widely used in the application of the Yakisugi technique), and Magnolia obovata (Japanese whitebark magnolia tree).

Japanese Carpentry 101: Final Food for Thought

One of the Japanese carpenters’ unique ways to display their woodworking skills is the keshomen which refer to the “decorative face” of just about any piece of wood. In a nutshell, the carpenters would strive to place the best face forward, and that’s the final accord or the most delicate and exquisite pearl in the crown of a finished piece of wood.

Keshomen is a brilliant example of the amazing way the Japanese carpenters would understand and treat the world. In every little mistake, they would choose to see a potential masterpiece; in every piece of damaged wood, they would choose to see a future work of art.

Certainly, Japanese carpentry would have never evolved so tremendously if it wasn’t for the mind-blowing dedication of the Japanese carpenters who were truly eager to study and upgrade the ancient craft.

Nevertheless, we all have the mutual responsibility to preserve and transfer the incredible knowledge of the gifted Japanese carpenters to the next generations.

The art of Japanese carpentry proves that everything is possible where there is intelligence, understanding, patience, and love not only for the good but also for the bad – not only for perfection but also for the flaws – because Yin cannot exist without Yang, and it is the vastness of our Minds that can turn what’s seemingly pitch black into pure white and vice versa.