The marae refers to a fenced-in complex of carved buildings, including the grounds that belong to a particular Maori tribe.

In fact, a marae can also belong to a sub-tribe or family of the Maori community.

Most noteworthy, the marae is a sacred place where important events such as celebrations, funerals, and meetings are held.

Nowadays, the traditional Maori meeting grounds are also used as educational workshops.

Luckily, numerous marae complexes across New Zealand provide tourists with the unique opportunity to experience first-hand the ancient customs of the Maori people.

Currently, over 600 000 people identify themselves as Maori. This makes up for approximately 15% of the national population of New Zealand. Thus, the Maori community is estimated to be the second-largest ethnic group on the islands.

Embraced by a certain sense of magic and mysticism, the meeting grounds of the ancient Maori people are much more than an ordinary building.

Instead, a marae represents the rich cultural heritage of the modern-day descendants of the Maori tribes who were the first to settle in New Zealand in the late 1250s.

Marae and Storytelling: The Invisible Thread

For a start, the art of storytelling has a very special place in the life of the ancient Maori people.

It is through the oral tradition of telling stories, myths, and legends that the cultural heritage of the natives was gradually formed.

But moreover, it was through storytelling that the rich culture was further preserved.

In fact, it is only fair to say that storytelling is the invisible thread that kept the Maori community close-knit.

Nevertheless, it was through the power of storytelling that the amazing Maori culture was kept alive and far away from oblivion even when faced with different threats such as land conflicts, social upheaval, and epidemics that started melting away the Maori ethnic group during the 1860s.

Fortunately, the Maori managed to recover after the accumulated tension, and the population began to rise in number with the start of the 20th century.

Back in the old times, the ancient Maori people were the first to inhabit the distant and remote islands of New Zealand.

Due to the isolated environment, the formation of collective memory has been of utmost significance for the nation.

Most probably, it would have never even been possible to nurture the vital collective memory of the people if it wasn’t for the magical stories that flowed from mouth to mouth, and, subsequently, transmuted from one generation to the next one.

Ultimately, the Maori meeting grounds – the marae – was the sacred place where the people could gather and share the fascination of sinking into a good story.

It is important to keep in mind that written language did not exist in the Maori society before the arrival of the first European explorers in the 15th century.

Hence, it was solely through the oral traditions that the community managed to preserve, form, and perform the extremely significant rituals that paid a tribute to the supernatural powers of the Universe, as well as the forces of nature.

But above all, the Maori meeting grounds were also used to commemorate the ancestors, whose powerful blessings and protection was highly valued.

Interestingly, Maori storytelling encompassed much more than the mere narrating of the stories.

Instead, various performances such as traditional dance (haka) and songs (waiata) were part of the storytelling practices of the natives.

Nevertheless, prayers known as karakia and poems were also cited during the ritual of storytelling.

And indeed, the art of Maori storytelling is a ritual since it is being looked upon as a sacred practice. Hence, the place for storytelling had to be sacred ground, too, and thus, the marae proved to work best for this purpose.

Most noteworthy, the marae was seen as tūrangawaewae – the place “to stand and belong.”

Exploring the Rich Symbolism of the Marae

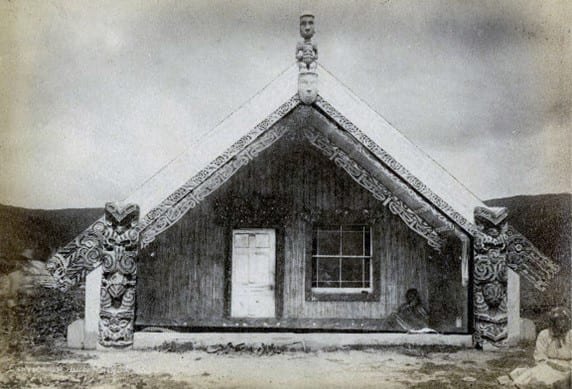

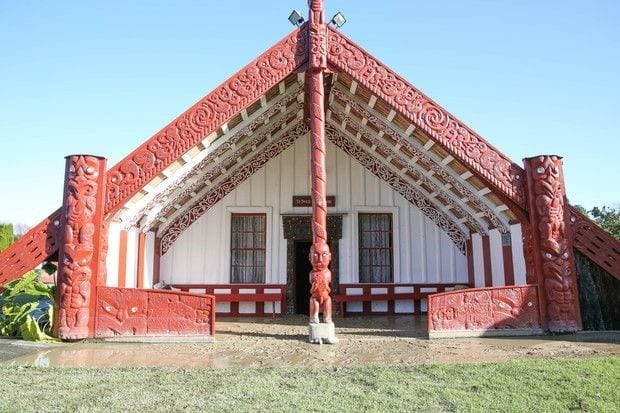

Apart from being seen the Maori’s sacred place to stand and belong, the marae is built according to strict rules.

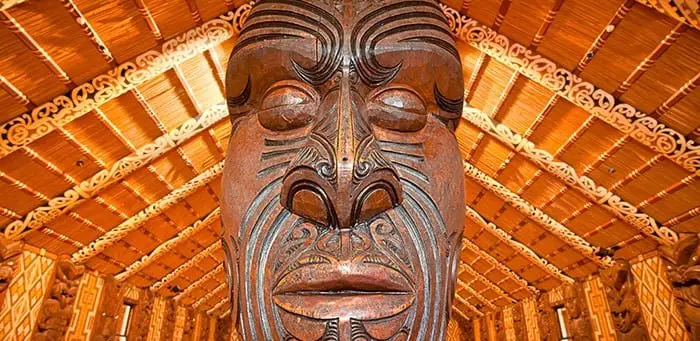

Each marae consists of an intricately carved meeting house called wharenui.

There is also an open space in front of the wharenhui that is called marae ātea.

Nonetheless, a dining hall compromising of an additional cooking area is also a significant part of the marae.

Finally, there a toilet and a shower block are necessary in order to ensure that the people can spend quality time together in the Maori meeting grounds.

The Soul of the Marae: The Wharenui

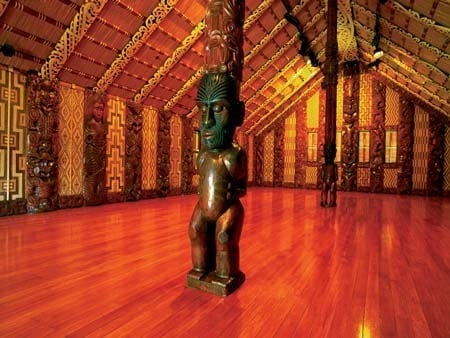

Even though it is not possible to compare the major parts of the Maori meeting grounds in terms of significance, the wharenui is, undoubtedly, one of the most symbolically rich elements.

The wharenui, or in other words, the carved meeting house was built in accordance with the structure of the human body.

Thus, for instance, the carved figure on the very top of the house referred to the head as part of the body.

Meanwhile, the front bargeboards of the meeting house were seen as arms that “welcomed” the visitors.

On the other hand, the short boards at the very front of the meeting house represented legs.

On another note, the large beam that ran all the way down to along the length of the roof was seen as the spine of the house.

Finally, the rafters reaching around the walls were seen as ribs.

Myths, Stories, and Legends that Come Alive through the Marae

The deep spiritual meaning of the marae is not solely related to the association of the different parts of the meeting house as a reference to the human body.

On the contrary, it is the rich symbolism of the finely carved figures that further enhance the magical sacredness of the Maori meeting grounds.

The figures that made up the Maori meeting grounds through the art of whakairo (wood carving) varied.

For example, some were made with a tribute to ancient Maori gods.

Traditionally, Maori people believed in the existence of many gods, and each was seen as the ruler of a particular natural force, phenomenon and/or crucial factor that determined the well-being of the natives.

Tūmatauenga is the god of war, fishing, hunting, and agriculture.

Tāwhirimātea is the god of the storms and the weather.

Tangaroa is the god of the sea but also the god of lakes and rivers, as well as the ruler of all the creatures that live in water.

Tāne-mahuta is the god of the forests and the birds.

Haumia-tiketike is the god of wild edible plants, who was seen as the guardian spirit of wild food.

Rongo is the god of peace and of cultivated plants.

Ruaumoko is the god of the seasons, the earthquakes, and the volcanoes.

Urutengangana is the god of the light.

Whiro is the god of darkness.

All of the Maori gods originated from Mother Earth – Papatūānuku, and Father Sky – Ranginui.

However, as we already briefly mentioned above, the carvings found in the traditional meeting houses of the Maori people were also often connected to the spirits of the ancestors.

Thus, significant people to a particular Maori tribe, sub-tribe or family could be commemorated through the carvings in the marae.

Nevertheless, the marae carvings could refer to the so-called whakapapa – the genealogy of the tribe, sub-tribe or family.

Nowadays, many Maori meeting grounds are opened to visitors, however, strict rules need to be followed closely as not to harm the sacredness of the amazing buildings.

For instance, food is not allowed to be consumed within the Maori meeting house, and it is a must for the visitors to remove their shoes at the very entrance.

Te Hau-ki-Tūranga: The Meeting House Built to Commemorate Rongowhakaata Chief

Built in the early 1840s at Ōrākaiapu pā, located close to Gisborne, the Te Hau-ki-Tūranga meeting house represents the talent and deep respect towards the ancient traditions employed by the master carver Raharuhi Rukupō.

It was in commemoration of Raharuhi Rukupō’s beloved brother – Tāmati Wāka Māngere, a Rongowhakaata chief that the meeting house was built.

Te Hau-ki-Tūranga is unique for it is the oldest example of a carved meeting house that was built with the use of steel tools. According to historians, metal was not among the materials that were utilized by the ancient Maori people.

It wasn’t before the arrival of the European explorers that metal was introduced to the Maori community and it quickly became an important part of their society.

Certainly, carving with the use of stone adzes and chisels must have been a painstakingly slow process that also required a tremendous dose of patience.

Yet, keeping in mind the lack of advanced instruments during the time when traditional Maori carving flourished, it only gets even more impressive to explore the mesmerizing patterns created by the master Maori carvers.

Unexpectedly, Te Hau-ki-Tūranga was confiscated by Native Minister J. C. Richmond in 1867, just years after it was built. The amazing carvings were then taken to Wellington.

During the 1930s, the Te Hau-ki-Tūranga was reconstructed under the direction of Āpirana Ngata.

Fortunately, over a century after being wrongfully removed under the command of Native Minister J.C. Richmond, the Te Hau-ki-Tūranga meeting house was returned to the people of Rongowhakaata by the year of 2017.

Legends and Stories about the Marae: Final Food for Thought

The marae is a living piece of history that is still being treated with tremendous respect by the Maori people.

Much more than merely an open space used as an assembly ground, the marae continues to be in the very spotlights of the pride that the natives take in their rich history and culture.

Just like the Maori meeting houses were built with various structures representing different parts of the human body, so is each meeting house seen as a place to honor the human side (the virtues) of deities and/or highly respected ancestors.

And while time passes and nothing remains the same, it is the traditions that keep the diversity of this planet alive, for mankind has evolved thanks to the unique intelligence that allows us not only to look for new, brighter horizons but also to remember.

It is through keeping the traditions alive that we can learn from those who inhabited this world long before we were born, for there are invaluable insights that time cannot erase or affect, even now, in the era of the most massive technological boom.

Probably the greatest lesson left by the gifted Maori carvers who marked the meeting grounds – the marae – with their dedication and skills – is the lesson of being able to pay a tribute to our roots, as well as the invisible forces of the Universe.